New analysis shows how updating industrial carbon pricing to make markets work better and keep participants in the systems will reduce more emissions and give industry greater certainty.

Canada’s industrial carbon pricing systems need an update. Although these policies are the country’s leading drivers of emissions reductions and important tools for attracting investment while costing consumers next to nothing, there is mounting evidence that they are not delivering to their full potential. The resulting uncertainty is a barrier to Canadian firms that could otherwise be investing in big low-carbon projects that preserve their long-term competitiveness.

Two data points show what needs fixing. First, according to fresh research conducted by the Canadian Climate Institute and Navius Research, it is increasingly clear that some markets behind these systems are on the brink of malfunction, undermining the certainty that investors need to support emissions-reducing projects. Second, some facilities that currently participate in these systems are poised to opt out, which would shrink the markets and diminish their impact.

The first threat to industrial carbon pricing: low credit prices

At the heart of Canadian industrial carbon pricing policies are markets where industrial facilities buy and sell permits (or credits) for their emissions. Those markets are the reason that these policies are also known as large-emitter trading systems, or LETS. Facilities that reduce their emissions earn credits and can sell them to facilities that are more emissions-intensive. The power of the market rests on the price of the credits, which act as a stick for those who pollute more and a carrot for those that invest in emissions reductions.

The problem is that credit prices aren’t evolving as intended. The Canadian Climate Institute has previously published research illustrating how credit prices in some LETS are expected to fall in the coming years, undermining the incentive to reduce emissions. The Institute has worked with Navius Research to update its previous analysis, and finds that the risks haven’t gone away. If anything, they have gotten worse.

Figure 1 displays the projected price of credits in Canada’s large-emitter trading markets in 2030 according to the latest research. To provide the certainty and return that investors are counting on, credit prices should rise to $170 per tonne of emissions in 2030. Yet that is not what happens in British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan, Ontario, and Nova Scotia. Instead, credit prices in these markets may settle at lower rates, weakening the incentive to invest in emissions-reducing projects.

Figure 1

Low credit prices are the result of having too many credits available for purchase on the market. As 440 Megatonnes has written before, all LETS markets have been designed to maintain a narrow balance of supply and demand. That makes systems vulnerable: small changes in economic outlook could easily lead to a higher supply of credits and depressed prices. Low credit prices don’t significantly lower costs—functioning LETS markets already have low costs by design, to protect competitiveness—but they do significantly undercut the reward for reducing emissions. That’s bad for investors, who need certainty to move forward on big projects.

The actual credit prices that emerge in these markets will depend on many factors, some of which are difficult to quantify or predict. The evolution of technology, market conditions, and certainty are all unpredictable and affect carbon markets. The lack of transparency around the internal workings of these markets also makes them harder to model. What is clear is that they face significant risks.

The problem may even be worse than this research suggests. Market data from Alberta and auction results from Quebec show that credit values in some LETS are already underperforming expectations. And Alberta is projecting lower-than-expected revenue from its TIER system in the coming years as participants use up excess credits that are banked in the system. If systems remain as they are, low credit prices are not going away.

The second threat to industrial carbon pricing: emitters leaving the system

Another looming challenge could compound the problems facing large-emitter trading markets: lower participation.

Canada’s large-emitter trading markets all contain two kinds of participating facilities: those that have to be there, and those that choose to be there. The second kind are known as opt-in facilities. Opt-in facilities are smaller than the facilities that are obliged to participate, but even those at the smaller end of the scale still produce nearly the same amount of greenhouse gases as 2,200 cars each year. Until recently, these facilities could choose either to pay the federal fuel charge or to opt into industrial pricing systems. Many chose to opt-in, because although industrial carbon pricing brought some additional administrative burden, its credit markets offered lower costs and even the potential to earn returns. But now that the fuel charge is gone, these facilities that have participated in LETS for years could simply opt out.

The loss of opt-in facilities could represent a significant loss of coverage, particularly in Alberta, which has many small oil and gas facilities but only obliges relatively high-emitting facilities (those emitting the equivalent of at least 22,000 cars per year) to participate in the credit market. According to this new analysis, as much as 31 megatonnes (Mt) worth of facilities could drop out of Canada’s LETS markets in the coming year. That represents around 9 per cent of Canada’s industrial emissions in 2023.

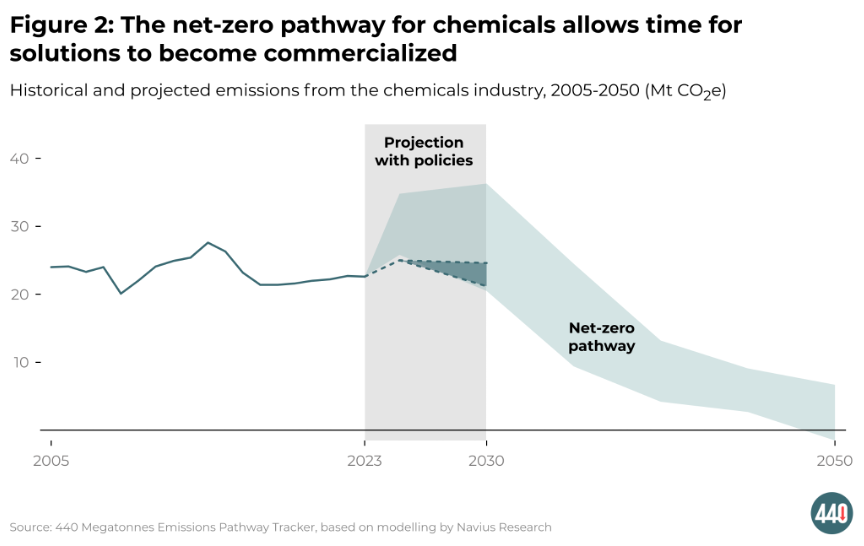

Figure 2 breaks down what the loss of opt-in facilities would mean for LETS coverage across the country.

Figure 2

Fortunately, policymakers can address these risks. If governments act to keep participants in the systems and modernize their markets, LETS can provide more certainty to investors and deliver greater emissions reductions. This new analysis finds that policy fixes to preserve the function and coverage of LETS would deliver up to 25 Mt of additional emissions reductions. That’s a conservative figure. As 440 Megatonnes has written previously, low credit prices could as much as halve the impact of LETS in 2030, so the benefits of tighter systems could be even greater.

The federal government should modernize industrial carbon pricing, and fast

The benefits of modernized large-emitter trading systems—and the risks attendant to their existing design—are too great to ignore. Rapid policy action can update industrial carbon markets so that they continue to support projects that are central to the long-term competitiveness of Canadian industry. In contrast, policy delay simply risks project delay.

The list of climate priorities never seems to grow shorter, but it sometimes grows clearer. In this case, the data are unambiguous: the top climate policy priority should be the modernization of industrial carbon pricing.

Ross Linden-Fraser is a Research Lead at the Canadian Climate Institute. Dale Beugin is Executive Vice President at the Canadian Climate Institute. Rick Smith is President of the Canadian Climate Institute.