This is the fifth and final instalment of our series on heavy industry.

Canada’s largest-emitting, most diverse heavy industry has many pathways to net zero, but they will all take time.

The chemical industry is the largest-emitting and most varied of Canada’s heavy industries.

It produces a huge range of products, including agricultural chemicals like fertilizers; industrial chemicals; formulated products like paints and soaps; and pharmaceuticals and medicines. In 2023, it was responsible for an estimated 22.6 megatonnes of emissions, representing 29 per cent of all emissions from heavy industry.

Chemicals have a vital role to play in the net zero transition, too. Chemical products have a huge number of uses, from the composites used in vehicles, solar panels, and wind turbines, to the chemical agents used in batteries and carbon capture.

This Insight discusses how the chemical industry can produce those valuable products while pursuing net zero emissions. The chemical industry described here is the same as the chemicals and fertilizer sub-sector in the National Inventory Report (NIR); 440 Megatonnes uses the simpler label since emissions from non-chemical fertilizers, such as potash, are captured in a separate part of the NIR.

The chemical industry has so far leaned on energy efficiency and carbon capture

There are more than 3,500 facilities making chemical products across Canada. But most of the industry’s emissions come from a small number of facilities, with the largest in Alberta and Ontario. The fertilizer sector, in particular, is more concentrated than the rest of the industry, with just nine facilities. Other chemical sub-sectors have many more producers, with the largest making petrochemicals. According to Clean Energy Canada, in 2022 the five top-emitting facilities accounted for 52 per cent of the emissions from chemical production.

The chemical industry generates so many emissions because it relies on fossil fuels not only for fuel, but also to provide the raw inputs for its products. For example, ammonia—the key ingredient in nitrogen fertilizers—is made by transforming methane gas into hydrogen, then reacting the hydrogen with nitrogen. Methane and hydrogen provide the energy and the key ingredients for the reaction, which releases additional process emissions.

Around 55 per cent of the chemical industry’s emissions come from the production of heat and electricity, while 43 per cent were process and other non-energy emissions that came from the use of fossil fuels in other ways, largely as feedstocks, lubricants, and solvents. Some chemical products such as nitrogen fertilizers also release emissions when they are used, but these do not count toward the industry’s emissions in the NIR.

Since 2005, emissions from the chemical industry have declined slightly. Figure 1 illustrates how the industry’s emissions are shaped by three key drivers: economic activity, energy intensity (or efficiency), and emissions intensity. The historical tab of the figure below shows that since 2005, rising economic activity put upward pressure on emissions, but this pressure was offset by efficiency improvements and some decarbonization from fuel switching.

Figure 1 also illustrates how the industry’s emissions could evolve between now and 2030. The projected tab of the figure shows that the industry’s emissions would decline further by 2030—if strong versions of climate policies are in place.

The emissions reductions shown in Figure 1, both historical and projected, depend on largely the same solutions. These data reflect facilities taking efficiency measures, cogenerating heat and electricity where possible, and in a small number of cases, installing carbon capture and storage. The path to net zero chemicals will rely on a broader and deeper range of solutions.

There are many possible solutions to cut emissions from chemicals, but no easy ones

There is no single approach to creating a net zero chemicals facility. Instead, there are multiple solutions, which may need to be combined in different ways depending on where a facility is located and what it produces.

Existing solutions will continue to play a role. As in the past, facilities could adopt efficiency measures and install carbon capture where feasible to reduce some of their emissions. But these interventions are unlikely to achieve net zero emissions on their own. Efficiency measures will only go so far, and it would be impractically expensive to apply carbon capture to all of a facility’s emissions.

The deepest emissions reductions in the chemical industry are those that replace fossil fuels, either by adopting lower-carbon feedstocks, switching to lower-carbon sources of energy like electricity, or both.

The largest current decarbonization project in the chemical industry relies on a combination of these solutions. This project, a planned expansion and retrofit to a Dow petrochemicals facility outside of Edmonton, will involve a mix of energy efficiency measures and fuel switching to hydrogen produced using carbon capture and storage.

Yet it may be some time before the most impactful solutions are widely adopted.

The main technical barrier is that chemical facilities face the dual challenge of replacing an energy source and a feedstock at the same time. Some potential solutions, like electrification, can only provide a source of energy and not feedstock—and are not yet commercialized anyway. Other solutions like hydrogen or biofuels could serve as both energy source and feedstock. Though even these solutions do not fully replace the role of fossil fuels in the manufacturing process, as facilities would need to find an alternative source of the carbon molecules that currently come from fossil fuels.

But beyond the technical barriers, there are practical ones. Currently, low-carbon hydrogen is very expensive and hard to procure in some parts of Canada, while biofuels are in low supply. And once the capital is acquired for a decarbonization project, it can be years before a proposal translates into construction.

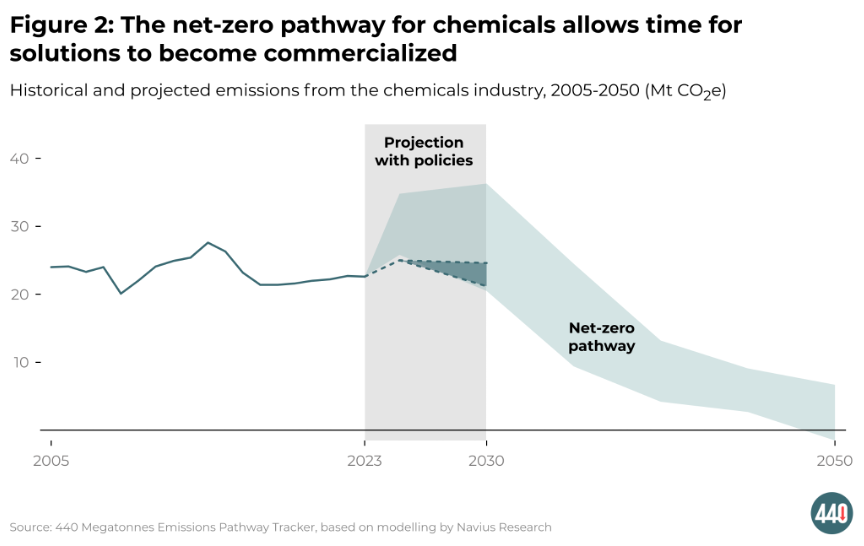

These challenges are visible in the chemical industry’s net zero pathway. Figure 2 illustrates how the net-zero pathway for chemicals leaves room for emissions increases in the near term, with accelerating reductions after 2030.

Net-zero chemicals are a long-term proposition, which calls for flexible, long-term policy signals.

Industrial carbon pricing is the most obvious policy lever that can support decarbonization in the chemical industry. Large-emitter trading systems are designed with the challenges of heavy industry in mind. They combine cost containment, technology neutrality, a long-term price signal, and the potential to earn revenue for emissions reducing projects.

Large-emitter trading systems play a key part in Dow’s decarbonization project. The emissions reductions from that project will allow the facility to earn credits that can be sold to other emitters. But the credits are only valuable so long as facilities have certainty that large-emitter trading markets will function as intended. Governments can provide additional certainty about the long-term prospects of these systems by adopting modernizing reforms, and through complementary measures like carbon contracts for difference.

But carbon pricing alone is not enough. Government investment in research and demonstration projects have played an important role in past reductions, and will continue to. Similarly, federal tax credits for hydrogen and carbon capture have already played a role in pushing existing projects forward. Given the variety of technology pathways that are available, the International Energy Agency notes that climate taxonomies can also help to steer investment to the most transition-aligned opportunities.

Policies focused on increasing the circular use of materials can also play an important role in reducing emissions from chemicals. The benefits are most obvious in the manufacture of plastics, where recycled material can reduce the need for virgin feedstock.

The economy of today and the economy of a net zero world will both rely heavily on products from the chemical industry. But the manufacture of those products won’t always have to generate emissions.

Ross Linden-Fraser is a Research Lead at the Canadian Climate Institute.