Insights for the federal government as it prepares to set Canada’s next emissions reduction target

The deadline for setting Canada’s 2035 emissions reduction target is fast approaching. Signatories to the Paris Agreement are required to set their next nationally determined contribution (NDC) by February 10, 2025, representing a progression from their previous NDC and the country’s “highest possible ambition”. The federal government has committed to set Canada’s 2035 target no later than December 1 this year, as part of its legislated climate accountability framework.

Setting evidence-based emissions reduction targets is a complex endeavour. Any rigorous target is rooted in climate science and the need to reduce emissions quickly. Ambitious targets matter because the signals we send can help mobilize action at home and abroad. Some of Canada’s major trading partners have already announced targets for 2035 and 2040, and it’s clear they are leveling up their ambition. Yet, targets also need to be achievable. Setting targets that governments can’t deliver through policy, or without high costs, could undermine follow-through.

In this week’s insight, we shine a light on those trade-offs to help inform the federal government’s thinking as it prepares to set the country’s 2035 target. While setting emissions reduction targets is important, they are only meaningful if governments also implement policies to meet them.

Target setting means balancing different priorities

As climate impacts and associated costs accelerate at a worrying pace across the country, it’s clear that Canada’s next emissions reduction target should be ambitious enough to meet the scale of the challenge. At the same time, it should be an achievable next step for Canada.

So what is the right balance between ambition and achievability?

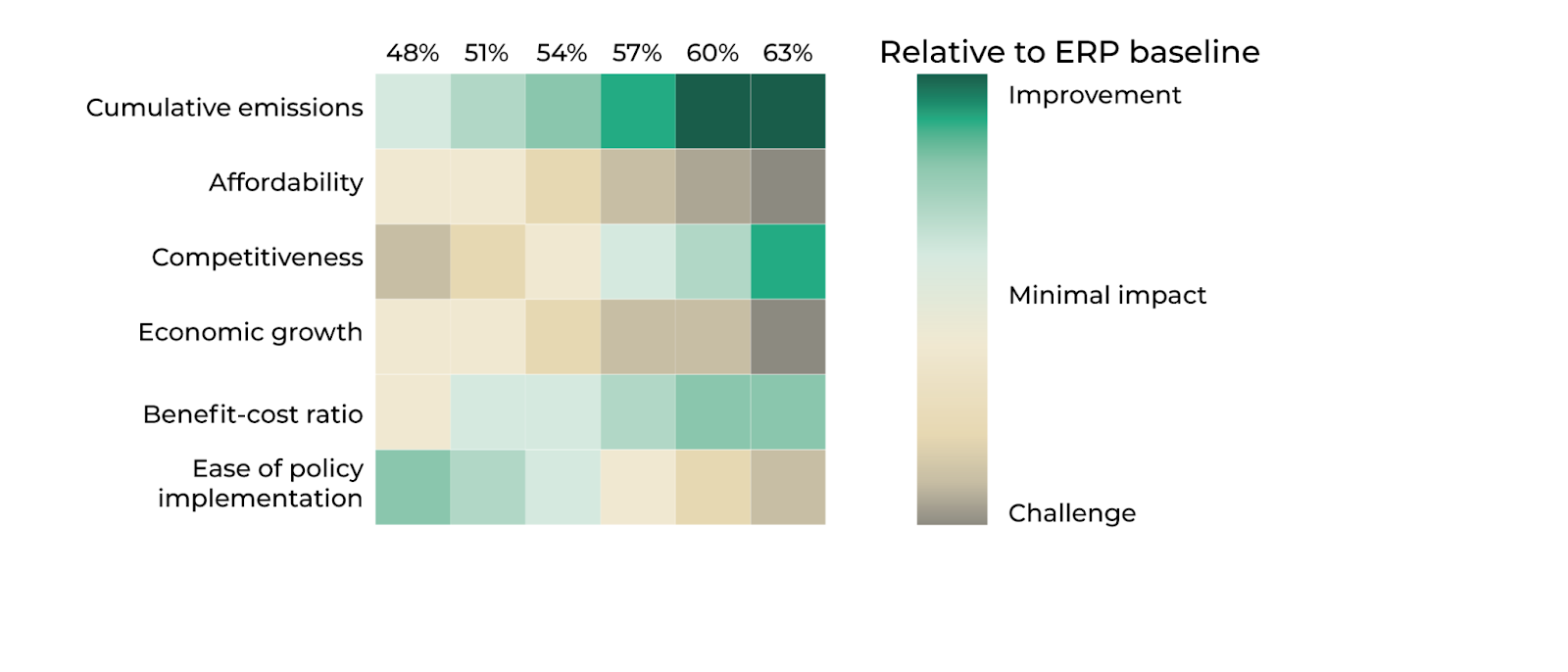

We were asked by the Net-Zero Advisory Body (NZAB) to evaluate options for Canada’s 2035 target to help inform their advice to the Minister of Environment and Climate Change. Working with Navius Research, we evaluated six potential targets against a set of criteria to examine the trade-offs of more or less ambition by 2035. The targets we assessed ranged from 48 to 63 per cent below 2005 levels.1 To assess long-term implications, we extended the emissions path from each target to a common net zero goal in 2050.

We evaluated the 2035 targets using six quantitative and qualitative indicators, informed by modelling analysis and expert input:

- Cumulative emissions: How many emissions are released, in total, between 2023 and 2050 for each target scenario?

- Affordability: How is household spending impacted by meeting weaker or stronger 2035 targets? Here we compared the net present value of the consumption portion of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) from 2023 to 2050, with higher levels indicating greater affordability for households.

- Competitiveness: How does achieving different targets impact short- and long-term investment in the Canadian economy? Here we measured the net present value of the investment portion of GDP from 2023 to 2050, with higher levels of investment indicating greater competitiveness for industry.

- Economic growth2: What is the impact of stronger or weaker targets on economic growth? For this indicator we looked at the net present value of GDP from 2023 to 2050 to assess how fast Canada’s economy is growing under different target scenarios.

- Benefit-cost ratio: What is the ratio of societal benefits of emissions reductions compared to economic costs? This indicator defines societal benefits as the change in emissions relative to the Emissions Reduction Plan (ERP) baseline multiplied by Canada’s social cost of carbon in each year. The costs are the economic cost of implementing mitigation measures, measured as the difference in total net GDP.

- Policy implementation: How much additional policy effort is required to meet the targets? How quickly do policies need to become more stringent? Can targets be achieved by strengthening policies already in place or do they require entirely new policies? We evaluated this indicator qualitatively, looking at the pathways to 2035 targets and assessing which policies would be required to meet them.

Figure 1 summarizes the results of our analysis by target and indicator, showing the outcomes from improvement to challenge relative to Canada’s current package of legislated, developing, and announced policies (“ERP baseline”).

Figure 1: Different 2035 targets will mean different long-term impacts across indicators

This figure underscores the balancing act inherent to target setting. While some targets demonstrate a marked improvement for certain indicators, they create a challenge for others.

For example, the steepest emissions reduction target we assessed—63 per cent below 2005 levels—unsurprisingly scores high on our cumulative emissions indicator. And while rapidly reducing emissions is critical to avoid the worst impacts of climate change–and can enhance Canada’s long-term competitiveness by spurring investment in clean technologies–front-loading Canada’s efforts could have implications for other indicators we care about, including household affordability and economic growth. A more aggressive 2035 target may require premature retirement of capital—including vehicles and heating equipment—leading to sharp increases in costs to consumers and businesses. In addition, if targets are so ambitious that they become disconnected from what is achievable, they can undermine confidence in governments’ ability to act on climate change.

At the same time, while setting a relatively less ambitious target may be more doable in the short-term, it also comes with risks. Delayed action pushes the hard work further into the future, creating challenges for Canada in meeting future emissions reduction targets, while also increasing the potential for stranded assets, such as fossil fuel resources and infrastructure. Lower ambition in 2035 could delay investment in emissions-reducing technologies, putting Canada at risk of falling behind in the global energy transition. It could also come with geopolitical and trade consequences if Canada is perceived to be doing less than its major trading partners and allies. And more greenhouse gas emissions in the short-term will only exacerbate global climate impacts.

An ambitious, yet achievable 2035 target for Canada

When it comes to target setting, there is no perfect solution—no one target will score high across all the criteria governments care about. Target setting inherently requires that governments wade through complex considerations and make trade-offs.

Looking across our subset of indicators, our analysis shows that a target range of 49 to 52 per cent below 2005 levels by 2035 balances the potential challenges that steeper targets may pose for affordability, economic growth, and policy implementation with the advantages of greater emissions reductions, Canadian competitiveness, and social benefits.

That’s not to say that achieving a 49 to 52 per cent reduction is taking the easy road. Even reaching a 49 per cent reduction in 2035 would require policies that are significantly more ambitious than those currently in place or proposed. Our 2023 independent assessment of the ERP found that Canada’s proposed policy package gets the country 85 per cent of the way to the 2030 target3. In a scenario where governments implement more ambitious policies to close the gap to Canada’s 2030 target, those policies would continue to drive emissions reductions post-2030, reaching 49 per cent below 2005 levels by 2035.4

In short, 49 to 52 per cent represents an ambitious, yet achievable target range for Canada.

Finally, a quick accounting aside: Canada’s targets are “net” emissions reductions. This means that targets are based on gross emissions from sectors, minus emissions removals or offsets. Figure 2 breaks down the gross and net emissions for our six 2035 targets, including 32 Mt of emissions removals from land-use, land-use change, and forestry (LULUCF) and 13 Mt of emissions removals from nature-based solutions and agricultural measures that enhance carbon sequestration. Both values are based on projections from Environment and Climate Change Canada.

However, net emissions estimates and data are highly uncertain and variable. For instance, Canada’s latest emissions data showed agricultural soils and crops as sources of emissions in 2022, rather than sinks, for the first time in almost 20 years. To reduce uncertainty in emissions reduction targets, governments should be transparent about assumed gross versus net emissions, work to improve measurement and accounting practices, and regularly track and report on progress.

Targets are only as effective as the policies in place to meet them

While it's not easy, well-founded emissions targets are worth the effort. These interim targets on the path to net zero are the foundation of climate accountability in Canada. By charting a course to long-term goals, targets can establish more certainty for industry, households, and other governments, and create incentives to invest in climate solutions. By establishing short-term goals against which to track progress, they can enhance government accountability to citizens for climate action, while creating regular opportunities to course correct. And by clarifying where actions need to ramp up to keep the country on a path to net zero emissions by 2050, they can help governments make more informed policy decisions.

Target setting and good governance are both important, but ultimately what matters most is that governments put policies in place to actually deliver on their climate commitments. Effective emissions reduction targets can, and should, challenge successive governments to internalize Canada’s net zero goal and the significant policy changes it requires.

Anna Kanduth was the Director of 440 Megatonnes at the Canadian Climate Institute. Dave Sawyer is the Principal Economist at the Canadian Climate Institute, Dale Beugin is the Executive Vice President at the Canadian Climate Institute, Brad Griffin is a 440 Megatonnes advisor and the Director of Simon Fraser University’s Canadian Energy and Emissions Data Centre. Alison Bailie is a Senior Research Associate at the Canadian Climate Institute.

Modelling data provided by Navius Research.

Footnotes

- 2005 emissions levels are based on the 2023 National Inventory Report.

- Economic growth does not account for damages from climate change. Damage costs are accounted for in the benefit-cost ratio indicator.

- At the time of the analysis, the Green Building Strategy had not yet been released and an illustrative representation reflecting the government’s mandate to implement regulatory standards to transition heating systems away from fossil fuels was used. The Green Building Strategy has now been released and is less stringent than the assumptions used in the Institute’s independent assessment of the ERP-PR. This means that the gap to 2030 will be larger than was found in the Institute’s independent assessment.

- To estimate 2035 emissions, we used post-modelling assumptions to extend emissions projections from 2030 to 2035.